I know most of the arguments against "Medicare for All." I’ve been making them for most of my professional life as a physician:

1) We don’t need it; our current mix bag of public and private insurance coverage is adequate

2) Disrupting the private insurance industry would result in too many job losses

3) The government cannot be trusted to run a program of this size

4) We don’t have buy-in from a majority of constituents

5) We simply can’t afford it.

I’ve said all of these for 30 years. I now know that I am wrong.

Health care policy can be simplified to answering the basic question of who gets covered and at what cost. Universal coverage was once championed only by the most progressive. Then came COVID-19.

COVID has taught us that every member of our society needs adequate health care. This is not just a progressive talking point, it is the reality of infectious disease: those without proper care run the risk of acquiring and transmitting the disease to the rest of us.

A service member with Combined Joint Task Force - Operation Inherent Resolve died in Syria, July 21.

Initial reports indicate the incident was not due to enemy contact.

The incident is under investigation.

It is CJTF-OIR policy to defer casualty identification procedures to the relevant national authorities after the next of kin have been notified.

Maj Gen Kenneth P. Ekman: Yeah, so on numbers, first I'll just tell you that our coalition and U.S. troop presence varies somewhat as we go through the various phases of the operation in both Syria and Iraq.

With regards to U.S. force presence in Iraq, that is something that we continually coordinate with the government of Iraq, and right now the number is 5,200. That is the enduring number that we've coordinated with our hosts, as they invited us here. I will tell you that those numbers are subject to some discussion as we progress our way through the campaign and as we work our way through the strategic dialogue that will negotiate and sort through our relationship with Iraq in the future.

With regards to Syria, those numbers are managed very carefully to make sure that we have sufficient forces to achieve our objectives in Syria, and those have been fairly stable for a while.

Lucas Tomlinson: So you said 5,200 in Iraq, and I didn't hear the number for Syria, General.

MAJ. GEN. EKMAN: Yeah, and we try to keep those pretty constant just because the numbers in Syria tend to point to specific capabilities. We're careful about how specifically we cite them, just given kind of our limited footprint there.

Thanks, though.

STAFF: Moving back to the phone line, Sylvie of AFP.

Q: Hello. Hello. Thank you.

You say that you are getting smaller, but answering Lucas' questions, you seem to say that the number is stable. So how are you getting smaller?

MAJ. GEN. EKMAN: Yes ma'am. Hey, thanks for your question. I didn't catch your name in the introduction.

And so we're at that point in our campaign -- and I covered this some in my opening remarks -- where we've been quite successful. We're continuing to transfer bases back to our Iraqi hosts. The most recent will be Basmaya, where the transfer ceremony occurs on the 25th of July. All of that is a sign of progress. What that has allowed us to do is to reduce our footprint here in Iraq. We're going to do that slowly, and we're going to do that in close coordination with the government of Iraq. But both for U.S. forces and coalition forces, we continue to work with our hosts so that our footprint here supports our mutual objectives.

Q: So excuse me, sir. I can follow up. So you are saying that it's not done yet. You are going to get smaller.

MAJ. GEN. EKMAN: Yes, ma'am. I think over time what you will see is a slow reduction of U.S. forces here in Iraq in coordination with our Iraqi hosts.

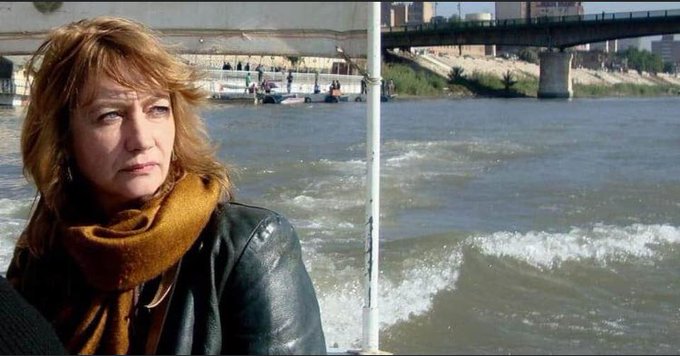

There can be no doubt that Hella Mewis, who has lived in Iraq for years, was aware of the omnipresent danger for foreigners. Many live barricaded behind thick concrete walls and barbed wire, protected and escorted by armed security personnel. Not so Hella Mewis. "I can't live without Baghdad," Mewis said in the interview. "If I leave Baghdad just for an hour, I already feel homesick!"

Born in then-East Berlin and educated as a theater manager, Mewis discovered her love for Iraq in 2013, when she went to Baghdad for a project sponsored by the Goethe Institut. "I got off the plane, set foot on Baghdad's soil and knew: This is home," Mewis was quoted two years ago in the German daily Frankfurter Rundschau (FR), which continues, "She came to Baghdad with the aim of giving the city of car bombs, suicide bombers and militias a different look."

Hella Mewis:

When we did the first installation, exhibition, people we were shocked and said This is not art. This is a question: what is art?

Simona Foltyn:

Bait Tarkib is run by Hella Mewis.

Hella Mewis:

The Iraqi society, some of them of course are conservative, but some of them are simply afraid to make a change. So this is why what we are trying to do — not to be afraid to make a change and other people will follow, I'm sure, they started to follow us.

Simona Foltyn:

Bait Tarkib organizes exhibitions and workshops to help emerging artists develop their portfolios and get exposure through events like the art walk. It receives funding from French and German cultural institutes, but not the Iraqi government.

Hella Mewis:

The government doesn't care at all about the young generation and art especially. Culture, no, nothing. Grants like we have in Europe so we have grants for the young generation, grants for cultural institutions, here is nothing.

Egypt has been facing off against Turkey not only in Libya, but also in Iraq, where the Turkish army has launched attacks in the north targeting the Kurdistan Workers Party, according to a June 15 Turkish Ministry of Defense statement. Meanwhile, Iraq has been accusing Turkey of violating Iraqi sovereignty and disrespecting the principles of good neighborly relations.

The Iraqi Parliament called on the UN Security Council July 6 to step in to stop the Turkish military incursions.

Egypt took advantage of the Iraqi-Turkish dispute to step up its efforts to cement ties with Iraq. Cairo offered diplomatic and political support to Baghdad against Turkey and the Egyptian Ministry of Foreign Affairs condemned the Turkish military intervention June 19.

In an earlier statement on July 3, the Egyptian Ministry of Foreign Affairs condemned ongoing Turkish violations of Iraqi sovereignty under what it called unfounded national security allegations and asserted that its actions are unacceptable and undermine regional peace and security.

Not by design, my book arrives at a time of national crisis, when polls suggest that Americans are fed up with the Trump administration’s pervasive amateurism. But Biden is not yet a shoo-in in the November election. Though the pandemic has revealed a nationwide yearning for straight talk and scientifically validated guidance, recoiling from the White House’s antics has not translated into a reacquired appreciation of old hands on the Hill like House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, for example—or, for that matter, of the media. Respect for such institutions remains abysmal.

Biden therefore remains afflicted with an indelible weakness—an inability to convince voters that 45 years’ worth of government experience represents a surefire cure for what now afflicts the United States. After all, what did all that expertise get Americans two decades ago? George W. Bush brought with him to the White House a highly skilled staff, featuring a star-studded foreign-policy team that had worked in government going back to the Ford administration. The new president managed to pass major bipartisan legislation with a Congress that was enjoying a relatively even-tempered interval between Newt Gingrich and the Tea Party. Meanwhile, newsrooms were well resourced and not yet convulsed by the internet. All of which is to say that Bush’s first year in office came at a time when Washington was at a peak of functionality.

[. . .]

During the campaign, Biden has passed on opportunities to elaborate his lessons learned from the Iraq experience. That’s not to say he hasn’t learned any. A nuclear physicist on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee’s payroll, Peter Zimmerman, had warned the committee’s chairman, Biden, of flaws in the prewar intelligence. Biden later apologized to Zimmerman for not listening. The question is, who would a President Biden listen to now?